- Carlos Luis Parra Calderón, University Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Andalusian Health System, Health Counseling, Spain

- Eiji Aramaki, NAIST, Japan

- Hercules Dalianis, Stockholm University, Sweden

- Stefan Schulz, Medical University of Graz, Austria

- Mariana Neves, Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR), Germany

- Aurélie Névéol, LIMSI-CNRS, Paris

- Karin Verspoor, University of Melbourne, Australia

- More members TBA.

Main Task Organizers

- Martin Krallinger, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

- Antonio Miranda, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

- Aitor Gonzalez-Agirre, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

- Marta Villegas, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

- Marvin Aguero, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

- Jordi Armengol, Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

Description of the Corpus

Datasets can be already Download it from Zenodo.

This CodiEsp corpus or data used for this track consists of 1,000 clinical case studies selected manually by a practicing physician and a clinical documentalist, comprising 16,504 sentences and 396,988 words, with an average of 396.2 words per clinical case. It is noteworthy to say that this kind of narrative shows properties of both, the biomedical and medical literature as well as clinical records. Moreover, the clinical cases were not restricted to a single medical discipline, and thus cover a variety of medical topics, including oncology, urology, cardiology, pneumology or infectious diseases.

The CodiEsp corpus is distributed in plain text in UTF8 encoding, where each clinical case is stored as a single file whose name is the clinical case identifier. Annotations are released in a tab-separated file with the following fields:

articleID ICD10-code

Tab-separated files for the third sub-track on Explainable AI contain an extra field that provides the position in the text of the text-reference:

articleID label ICD10-code text-reference reference-position

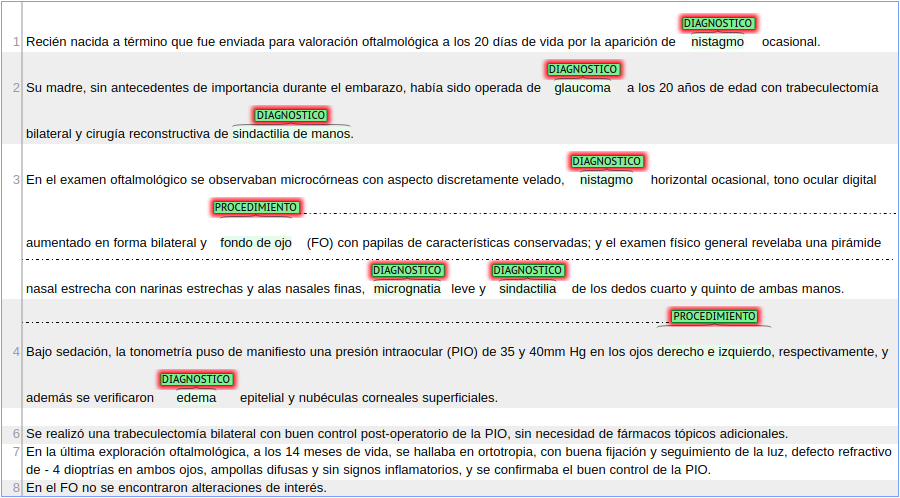

Below we show an example of an annotated clinical case in the Brat visualization tool.

The CodiEsp corpus has 18,483 annotated codes, of which, 3427 are unique. These are divided into two groups:

- ICD10-CM codes (CIE10 Diagnóstico in Spanish). They are codes belonging to the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification and are tagged as DIANOSTICO.

- ICD10-PCS codes (CIE10 Procedimiento in Spanish). They are codes belonging to the International Classification of Diseases, Procedure codes (related to procedures performed in hospitals) and their tag is PROCEDIMIENTO.

Moreover, codes are annotated with a reference in the text that justifies the coding decision. There are continuous and discontinuous references, having the latter several parts distributed along with the text.

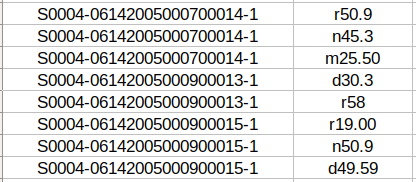

In the case of the previous clinical case, the provided tab-separated file for the first sub-track (ICD10-CM coding) contains the following information:

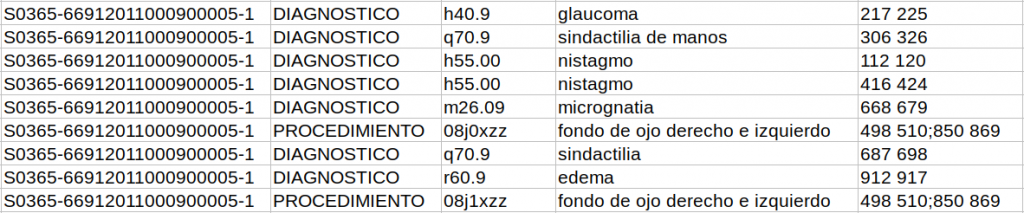

In the third sub-track, the tab-separated file has extra columnS of information that specify the reference itself and the label it has (DIAGNOSTICO or PROCEDIMIENTO) and the position in the text where the reference is taken from. In the case of discontinuous references, different sections of the reference are separated by a semicolon.

The entire CodiEsp corpus has been randomly sampled into three subsets, the training, development and test set. The training set comprises 500 clinical cases, and the development and test set 250 clinical cases each. Together with the test set release, we will release an additional collection of more than 2,000 documents (background set) to make sure that participating teams will not be able to do manual corrections and also promote that these systems would potentially be able to scale to larger data collections.

Datasets

Datasets can be already downloaded from Zenodo.

The CodiEsp corpus has been randomly sampled into three subsets: the train, the development, and the test set. The training set contains 500 clinical cases, and the development and test set 250 clinical cases each.

CodiEsp corpus will be published translated to English during the week previous to the test set release (10-14 February).

Train set

The train set is composed of 500 clinical cases. Download it from Zenodo.

Development set

The Development set is composed of 250 clinical cases. Download it from Zenodo.

Test and Background set

The test set has 250 clinical cases. The background set is composed of 2,751 clinical cases. Download them from Zenodo.

Test set with Gold Standard annotations

The Test set is with Gold Standard annotations is composed of 250 clinical cases. Download it from Zenodo.

Additional Datasets

Additional set 1 – Abstracts with ICD10 codes.

To expand the train and development corpora, a JSON file with abstracts from Lilacs and Ibecs with ICD10 codes (ICD10-CM and ICD10-PCS) associated with them (CIE10 in Spanish) is provided. Download it from ZENODO.

The format of the JSON file is the following:

{'articles':

[{'title': 'title',

'pmid': 'pmid',

'abstractText': 'abtract (in Spanish)',

'Mesh':

[{'Code': 'MeSHCode',

'Word': 'reference',

'CIE': [CIE10_1, CIE10_2, ...]},

...]

},

...]

}

There are 176 294 abstracts with an average of 2.5 ICD10 codes per abstract.

In addition, the same additional dataset is provided in the CodiEsp format: abstracts are distributed in individual UTF-8 text files and a tab-separated file summarizes the JSON information in four columns:

articleID label ICD10-code word

Publications

We would like to inform you that CodiEsp’s proceedings will be part of the CLEF 2020 conference. In particular, it will be part of the CLEF eHealth series. The schedule is therefore adjusted according to the CLEF schedule. CodiEsp’s proceedings will also be adjusted to CLEF requirements and they will be published in Springer LNCS Series. As soon as further information about proceedings is ready on the CLEF webpage, it will be published here.

Paper submission schedule:

| Date | Event | Link |

|---|---|---|

| July 17, 2020 | Participants’ working notes papers submitted | https://easychair.org/conferences/?conf=clef2020 |

| August 14, 2020 | Notification of acceptance participant papers | TBA |

| August 28, 2020 | Camera ready paper submission | TBA |

| September 22-25, 2020 | CLEF 2020 | https://clef2020.clef-initiative.eu/index.php |

Proceedings Details:

- Submission instructions: https://temu.bsc.es/codiesp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/codiesp-codiesp-working-notes-submission-instructions.pdf

- Structure: LaTex template

- Last year Proceedings: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-28577-7

Task Overview cite

@InProceedings{CLEFeHealth2020Task1Overview,

author={Antonio Miranda-Escalada and Aitor Gonzalez-Agirre and Jordi Armengol-Estapé and Martin Krallinger},

title="Overview of automatic clinical coding: annotations, guidelines, and solutions for non-English clinical cases at CodiEsp track of {CLEF eHealth} 2020",

booktitle = {{Working Notes of Conference and Labs of the Evaluation (CLEF) Forum}},

series = {{CEUR} Workshop Proceedings},

year = {2020}, }

Lab Overview cite

@InProceedings{CLEFeHealth2020LabOverview,

author={Lorraine Goeuriot and Hanna Suominen and Liadh Kelly and Antonio Miranda-Escalada and Martin Krallinger and Zhengyang Liu and Gabriella Pasi and Gabriela {Saez Gonzales} and Marco Viviani and Chenchen Xu},

title="Overview of the {CLEF eHealth} Evaluation Lab 2020",

booktitle = {{Experimental IR Meets Multilinguality, Multimodality, and Interaction: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference of the CLEF Association (CLEF 2020) }},

series = {LNCS Volume number: 12260},

year = {2020},

editor = {Avi Arampatzis and Evangelos Kanoulas and Theodora Tsikrika and Stefanos Vrochidis and Hideo Joho and Christina Lioma and Carsten Eickhoff and Aurélie Névéol and Linda Cappellato and Nicola Ferro}

}

Workshops

MIE2020

CodiEsp setting and results will be presented at the workshop First Multilingual clinical NLP workshop (MUCLIN) at MIE2020. This year, MIE is virtual thanks to the collaboration of EFMI. Please, register at https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_xSrKgnjsQhGP_ZUsQUS3fQ

This workshop will have two parts:

First, there will be a presentation of the shared task overview and proposed approaches.

Then, there will be a 30 minutes panel discussion with experts on the role of the shared tasks to promote clinical NLP, resources, tools, evaluation methods.

See EFMI program.

See MUCLIN program.

CLEF eHealth

CodiEsp is included in the 2020 Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum, this year, an online-only event.

Participants’ working notes will be published in the CEUR-WS proceedings (http://ceur-ws.org/). Task overview paper will also be published in the CEUR-WS proceedings.

@InProceedings{CLEFeHealth2020Task1Overview,

author={Antonio Miranda-Escalada and Aitor Gonzalez-Agirre and Jordi Armengol-Estapé and Martin Krallinger},

title="Overview of automatic clinical coding: annotations, guidelines, and solutions for non-English clinical cases at CodiEsp track of {CLEF eHealth} 2020",

booktitle = {{Working Notes of Conference and Labs of the Evaluation (CLEF) Forum}},

series = {{CEUR} Workshop Proceedings},

year = {2020},

}

Since CodiEsp is part of CLEF eHealth lab, lab overview paper will be published in the Springer LNCS proceedings.

@InProceedings{CLEFeHealth2020LabOverview,

author={Lorraine Goeuriot and Hanna Suominen and Liadh Kelly and Antonio Miranda-Escalada and Martin Krallinger and Zhengyang Liu and Gabriella Pasi and Gabriela {Saez Gonzales} and Marco Viviani and Chenchen Xu},

title="Overview of the {CLEF eHealth} Evaluation Lab 2020},

booktitle = {{Experimental IR Meets Multilinguality, Multimodality, and Interaction: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference of the CLEF Association (CLEF 2020)

}},

series = {LNCS Volume number: 12260},

year = {2020},

editor = {Avi Arampatzis and Evangelos Kanoulas and Theodora Tsikrika and Stefanos Vrochidis and Hideo Joho and Christina Lioma and Carsten Eickhoff and Aurélie Névéol and Linda Cappellato andNicola Ferro},

}

Journal Special Issue

The planned workshop functions as a venue for the different types of contributors, mainly task providers and solution providers, to meet together and exchange their experiences.

We expect that investigation on the topics of the task will continue after the workshop, based on new insights obtained through discussions during the workshop.

As a venue to compile the results of the follow-up investigation, a journal special issue will be organized to be published a few months after the workshop. The specific journal will be announced after negotiation with publishers.

Contact and FAQ

Email Martin Krallinger to: encargo-pln-life@bsc.es

FAQ

- How to submit the results?

Results will be submitted through EasyChair. We will provide further submission information in the following days. - Can I use additional training data to improve model performance?

Yes, participants may use any additional training data they have available, as long as they describe it in the working notes. We will ask to summarize such resources in your participant paper foreHealth CLEF and the short survey we will share with all teams after the challenge. - The task consists of three sub-tasks. Do I need to complete all sub-tasks? In other words, If I only complete a sub-task or two sub-tasks, is it allowed?

Sub-tasks are independent and participants may participate in one, two or the three of them. - Are there unseen codes in the test set?

Yes, there may be unseen codes in the test set. We performed a random split of training, validation and test. 500 documents were to train, 250 to validation and 250 to test. - Why is number of training and development dataset (500 and 250) low in comparison with testing data (circa 3000)?

It is actually not. There are 250 test set documents. However, we have added the background set (circa 2700), to prevent manual predictions. Systems will only be evaluated on the 250 test set documents. - How can I submit my results? Can I submit several prediction files for each sub-task?

You will have to create a ZIP file with your predictions file and submit it to EasyChair (see step-by-step guide).

Yes, you can submit up to 5 prediction files, all in the same ZIP. - Should prediction files have headings?

No, prediction files should have no headings. See more information about prediction file format at the submission page.

Schedule

TBD

Additional Resources

Evaluation Script

- Official evaluation script: Available at GitHub.

This is the official evaluation script of the task. See Evaluation for more information about the evaluation and Evaluation library and Examples sections for even more clarity.

Additional Datasets

- Spanish abstracts with ICD10 codes. Download it from Zenodo.

It is a collection of abstracts in Spanish with ICD10 codes.

It can be used to improve system training.

For more information, see the Datasets page or Zenodo webpage. - Translated to Spanish corpus with ICD10 codes. Download it from Zenodo.

It is a collection of abstracts in Spanish (machine-translated from English) with ICD10 codes.

It can be used to improve system training. - English, Spanish and Portuguese clinical case reports (639 for each language) annotated with medical diagnostic codes from the ICD10-CM. Download from GitHub.

It is a collection of abstracts in 3 languages with ICD10 codes.

It can be used to improve system training.

Linguistic Resources

- CUTEXT. See it on GitHub.

Medical term extraction tool.

It can be used to extract relevant medical terms from clinical cases. - SPACCC POS Tagger. See it on Zenodo.

Part Of Speech Tagger for Spanish medical domain corpus.

It can be used as a component of your system. - NegEx-MES. See it on Zenodo.

A system for negation detection in Spanish clinical texts based on NegEx algorithm.

It can be used as a component of your system. - AbreMES-X. See it on Zenodo.

Software used to generate the Spanish Medical Abbreviation DataBase. - AbreMES-DB. See it on Zenodo.

Spanish Medical Abbreviation DataBase.

It can be used to fine-tune your system. - MeSpEn Glossaries. See it on Zenodo.

Repository of bilingual medical glossaries made by professional translators.

It can be used to fine-tune your system.

Terminological Resources

- Valid codes for the task. Download it here.

- Spanish Ministry of Health official CIE10 browser. See the documentation page for the 2018 version.

ICD10 terminology in Spanish is named CIE10. It is managed by the Ministry of Health. - Diseases and symptoms lexicon with MESH and ICD10 codes. List of disease and symptoms terms extracted from Spanish clinical texts. They are mapped to MESH and from MESH to ICD10.

It can be used as gazetteers or dictionaries.

Download it here. - More soon published.

Established Coding Systems

Other Relevant Systems

Evaluation

The CodiEsp evaluation script can be downloaded from GitHub.

Please, make sure you have the latest version.

Participants will submit their predictions for the test set and the background set. Both will be released together so that they cannot be separated to make sure that participating teams will not be able to do manual corrections and also that these systems are able to scale to larger data collections. However, predictions will only be evaluated for the test set.

CodiEsp-D and CodiEsp-P: MAP

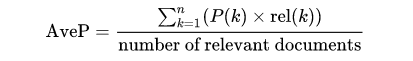

For sub-tracks CodiEsp-D and CodiEsp-P, participants will submit their coding predictions ranked. For every document, a list of possible codes will be submitted ordered by confidence or relevance (codes not in the list of valid codes will be ignored). Then, since these sub-tracks are ranking competitions, they will be evaluated on a standard ranking metric: Mean Average Precision (MAP).

MAP is the most established metric in ranking problems. It stands for Mean Average Precision, where the Average Precision represents the average precision of a document at every position in the ranked codes. That is, precision is computed considering only the first ranked code; then, it is computed considering the first two codes, and so on. Finally, precision values are averaged over the number of codes in the gold standard (the relevant number of codes):

MAP is the most standard ranking metric among TREC community and it has shown good discrimination and stability [1]. Individual average precisions are equivalent, in the limit, to the area under the precision-recall curve; therefore, MAP represents the mean of the areas under the precision-recall curve.

It favors systems that return relevant documents fast [2] since those systems would have a higher average precision for every clinical case of the test set. Finally, contrary to other ranked evaluation metrics, it is easy to understand if precision and recall concepts are already understood; it takes into account all relevant retrieved documents; and information is stored in a single point, which eases comparison among systems.

CodiEsp-X: F-score

For the Explainable AI sub-track, the explainability of the systems will be considered, in addition to their performance on the test set.

To evaluate both explainability and performance of a system, systems have to provide a reference in the text that supports the code assignment (codes not in the list of valid codes will be ignored). That reference is cross-checked with the true reference used by expert annotators. Only correct codes with correct references are valid. Then, Precision, Recall, and F1-score are used to evaluate system performance (F-score is the primary metric).

Precision (P) = true positives/(true positives + false positives)

Recall (R) = true positives/(true positives + false negatives)

F-score (F1) = 2*((P*R)/(P+R))

Special cases:

- In case one single code has several references in the Gold Standard file, acknowledging only one is enough.

- For discontinuous references, the metric considers that the reference starts at the start position of the first fragment of the reference. Equivalently, the reference is considered to end at the final position of the last fragment of the reference.

References

[1] Christopher D. Manning, Prabhakar Raghavan and Hinrich Schütze, Introduction to Information Retrieval, Cambridge University Press. 2008.

[2] L. Dybkjær et al. (eds.), Evaluation of Text and Speech Systems, 163–186, Springer. 2007.