Annotation Guidelines

This page gives an overview of the annotation and normalization scheme and process of the MEDDOPLACE corpus. More detailed information is available in the Annotation Guidelines, a 60+ pages long file that documents the corpus’s creation and annotation process and methodology.

The MEDDOPLACE guidelines were created by clinical and linguistic experts, who reviewed several location-related corpora to create an annotation scheme that was detailed enough and specialized to the clinical domain. After their definition, the guidelines were refined in 5 rounds of inter-annotator agreement of 20 documents each (10% of the corpus), with a final agreement of 88% for the annotation, 80% for the classification and 85% for the normalization. Additionally, once the manual annotation phase was finished, the corpus was thoroughly revised in a post-processing step to maximize consistency.

This page has three parts:

- Annotation

- Normalization

- Classification

1. Annotation

In terms of named-entity recognition annotation, MEDDOPLACE could be divided in two separate set of labels: locations and location-related information.

Location annotation

The MEDDOPLACE location annotation scheme takes after previous corpora that also annotate locations such as ACE (Doddington et al., 2004) and the BBN corpus (Weischedel and Brunstein, 2005).

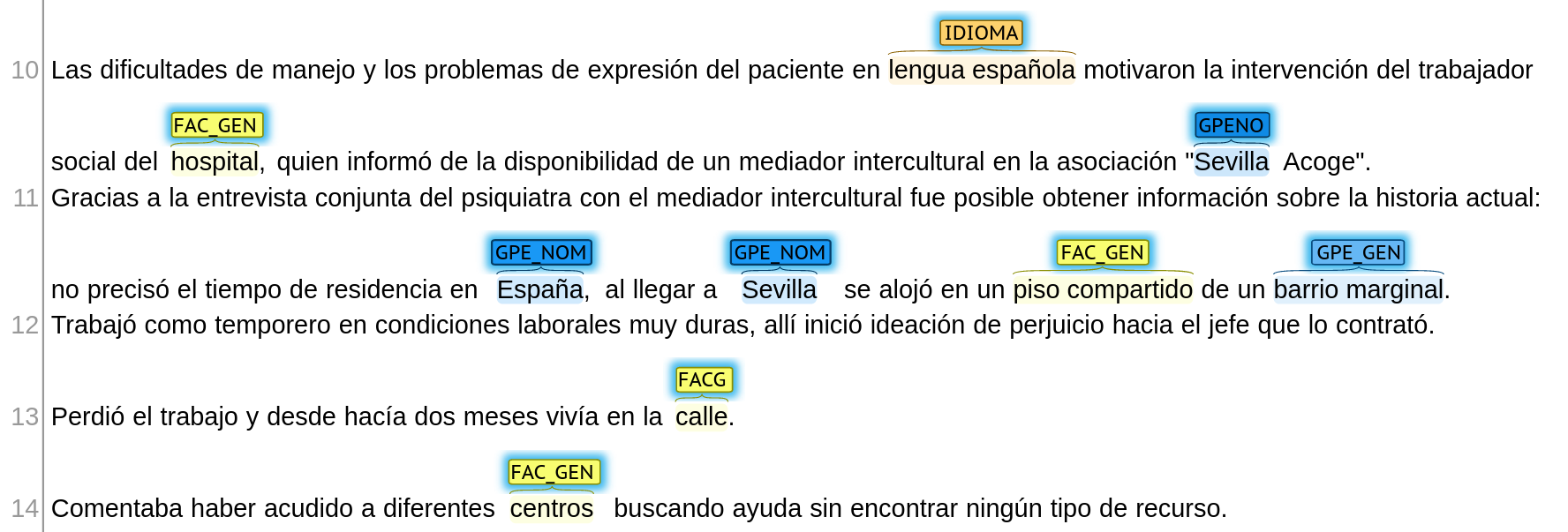

From ACE, we take the granular division between three location types: geopolitical entities (GPE — includes human-made geographical divisions like countries and cities), facilities (FAC — includes human-made constructions and buildings like airports, hospitals or stores) and geographical accidents (GEO — includes natural geographical accidents, habitats and similar locations like mountains or oceans).

From the BBN (and OntoNotes), we take the division between named entities (NOM — includes proper names like “Spain” or “Hospital Clínic de Barcelona”) and generic entities (GEN — includes common names like “mental health facility” or “rural area”). In our annotation, each of the three location types is divided in two subtypes. This two-way division allows flexibility to group annotations either by location type or by name type, making it possible to detect locations with the desired granularity.

All in all, there is a total of six location labels: named geopolitical entities (GPE_NOM), generic geopolitical entities (GPE_GEN), named geographical accidents (GEO_NOM), generic geographical accidents (GEO_GEN), named facilities (FAC_NOM) and generic facilities (FAC_GEN).

Location-related information annotation

There is more information related to locations, spatial movements, patient origin, … in text other than name places. For that reason, we include four extra labels which allow a better characterization of everything related to locations from a clinical perspective:

- Clinical departments (DEPARTAMENTO label): A lot of information in clinical texts refers to specific services (“emergency service”), departments (“cardiology department”), specialties (“Neurology”) or parts within a hospital (“emergency room”). These concepts are sometimes actual places (like a doctor’s office), but they can also refer to organizations or clinical teams. In spite of this, their relevance in clinical information extraction is evident, as they can help characterize the different aspects of medicine that have played a role in a patient’s route.

- Travels and patient movements (TRANSPORTE label): This is a fuzzy label that contains information related to patient movements, including movement words (“trip”, “transfer”), means of transportation () and other related words and expressions.

- Communities (COMUNIDAD label): This label includes sociodemographic information that is sometimes related to patient origin or current residence, such as demonyms (e.g. “French”), religions (e.g. “muslim”) or ethnicities (e.g. “caucasian”).

- Languages (IDIOMA label): The language(s) spoken by the patient can also have a great impact on their treatment and its quality. This label includes both languages and some mentions related to linguistic problems (such as “language barrier”).

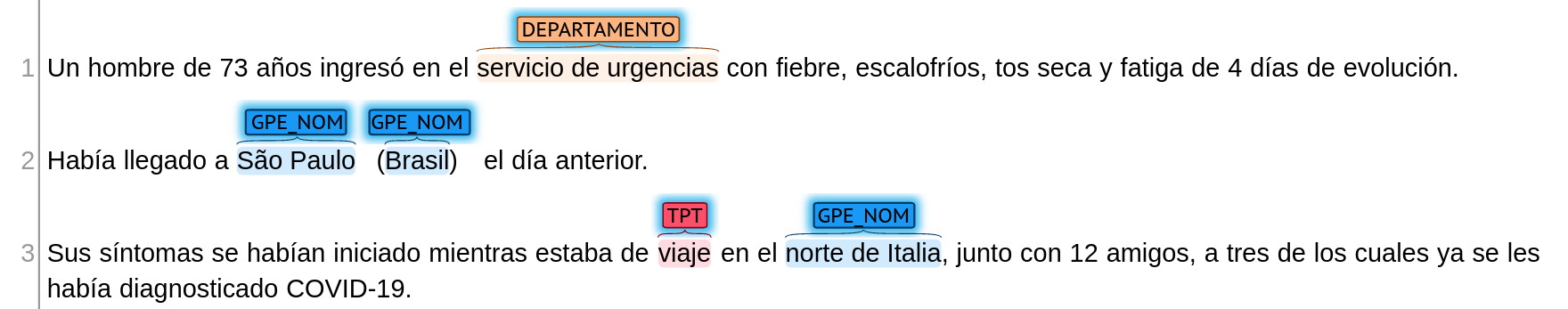

A 73-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department with fever, chills, dry cough and fatigue of 4 days' duration.

He had arrived in São Paulo (Brazil) the previous day.

His symptoms had started while he was travelling in northern Italy, together with 12 friends, three of whom had already been diagnosed with COVID-19.

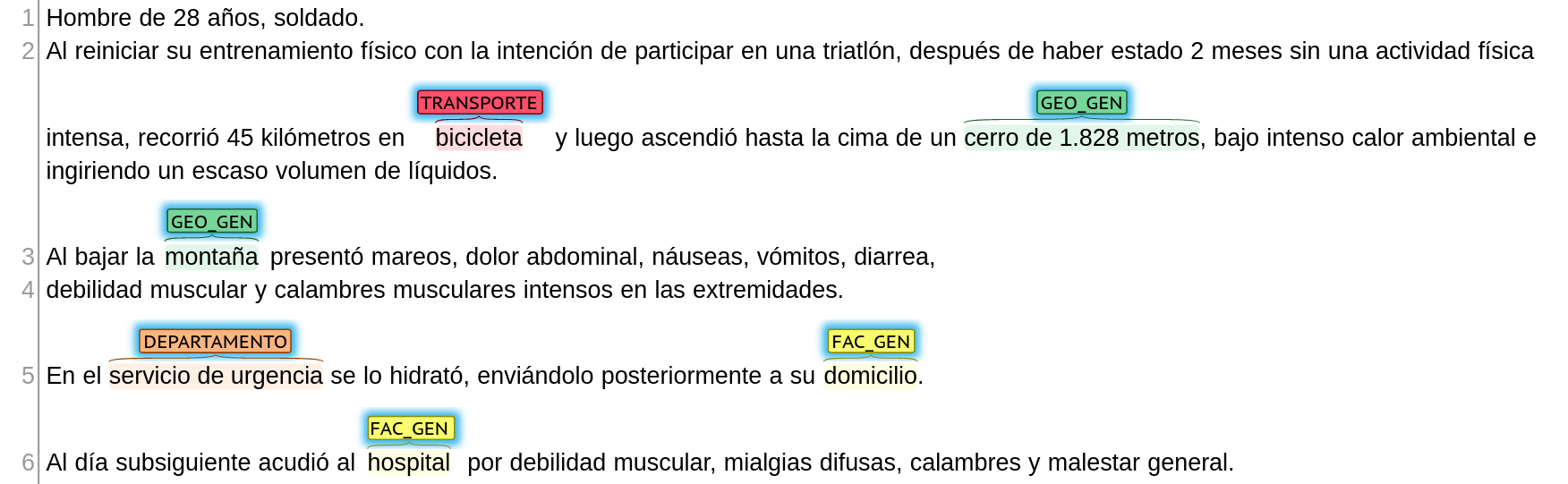

28-year-old male soldier.

When he restarted his physical training with the intention of participating in a triathlon, after 2 months without intense physical activity, he rode 45 kilometres on a bicycle and then climbed to the top of a 1,828-metre hill, under intense ambient heat and ingesting a small volume of liquids.

On his way down the mountain he experienced dizziness, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea,

muscle weakness and severe muscle cramps in his limbs.

He was hydrated at the emergency department and sent home.

The next day he came to the hospital with muscle weakness, diffuse myalgia, cramps and general malaise.

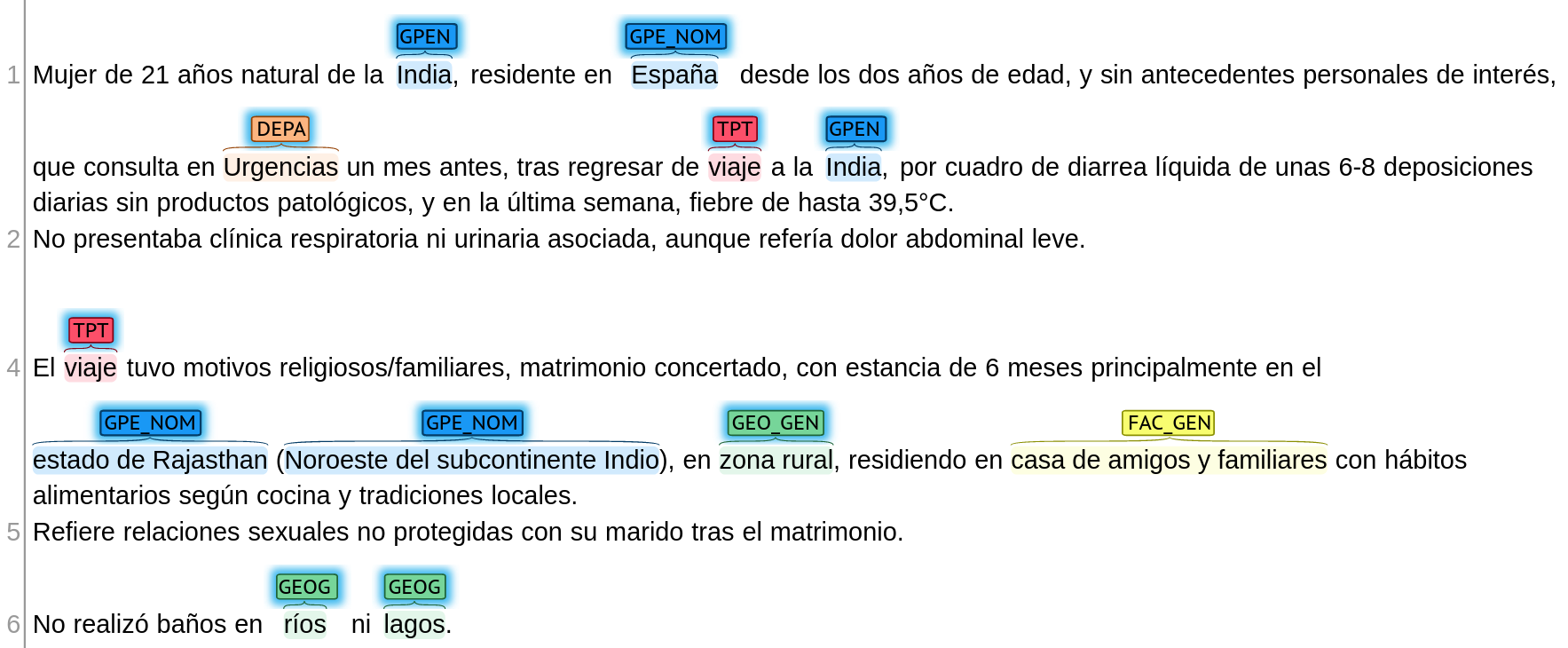

A 21-year-old woman from India, resident in Spain since the age of two, with no personal history of interest, consulted the emergency department one month earlier, after returning from a trip to India, for liquid diarrhoea of 6-8 stools per day without pathological products, and in the last week, fever of up to 39.5°C.

She had no associated respiratory or urinary symptoms, although she reported mild abdominal pain.

The trip was for religious/family reasons, arranged marriage, with a stay of 6 months mainly in the state of Rajasthan (North West of the Indian subcontinent), in a rural area, residing in the homes of friends and relatives with eating habits according to local cuisine and traditions.

She reports unprotected sexual relations with her husband after marriage.

She did not bathe in rivers or lakes.

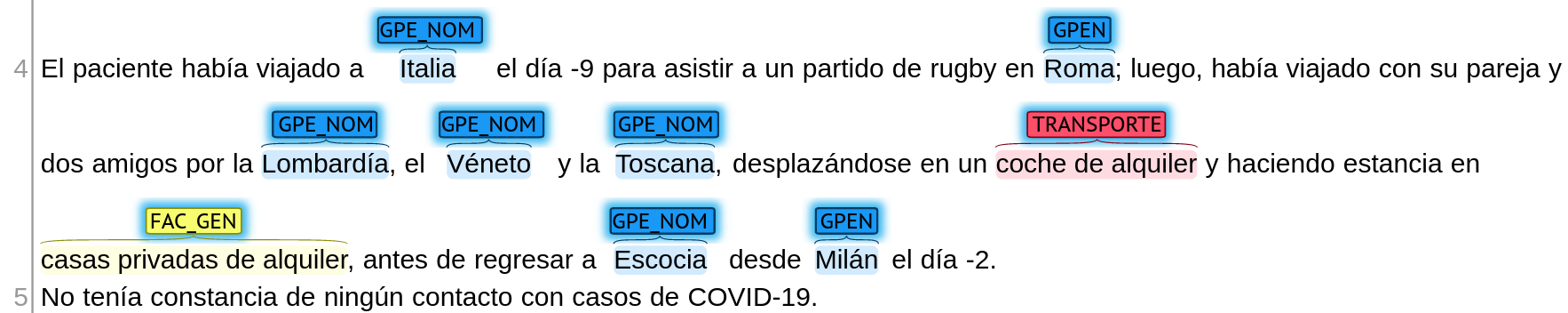

The patient had travelled to Italy on day -9 to attend a rugby match in Rome; he had then travelled with his partner and two friends through Lombardy, Veneto and Tuscany, travelling in a rented car and staying in private rented houses, before returning to Scotland from Milan on day -2.

He was not aware of any contact with COVID-19 cases.

The patient's difficulties in managing and expressing himself in Spanish prompted the intervention of the hospital social worker, who informed him of the availability of an intercultural mediator at the association "Sevilla Acoge".

Thanks to the joint interview between the psychiatrist and the intercultural mediator, it was possible to obtain information about his current history: he did not specify how long he had been living in Spain; when he arrived in Seville, he stayed in a shared flat in a marginal neighbourhood.

He worked as a seasonal worker in very hard working conditions, where he started to think of harming the boss who hired him.

He lost his job and had been living on the street for two months.

He said that he had gone to different centres looking for help without finding any kind of help.

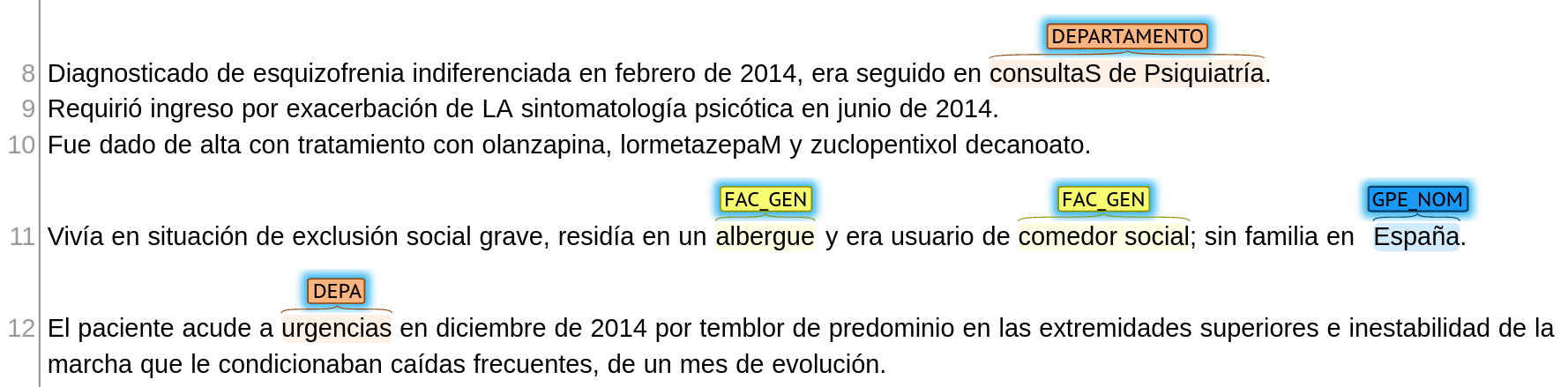

Diagnosed with undifferentiated schizophrenia in February 2014, he was being followed in Psychiatry.

He required admission for exacerbation of psychotic symptoms in June 2014.

He was discharged with treatment with olanzapine, lormetazepaM and zuclopenthixol decanoate.

He lived in a situation of severe social exclusion, resided in a shelter and was a user of a soup kitchen; he had no family in Spain.

The patient came to the emergency department in December 2014 due to tremor predominantly in the upper limbs and gait instability that led to frequent falls, which had been going on for a month.

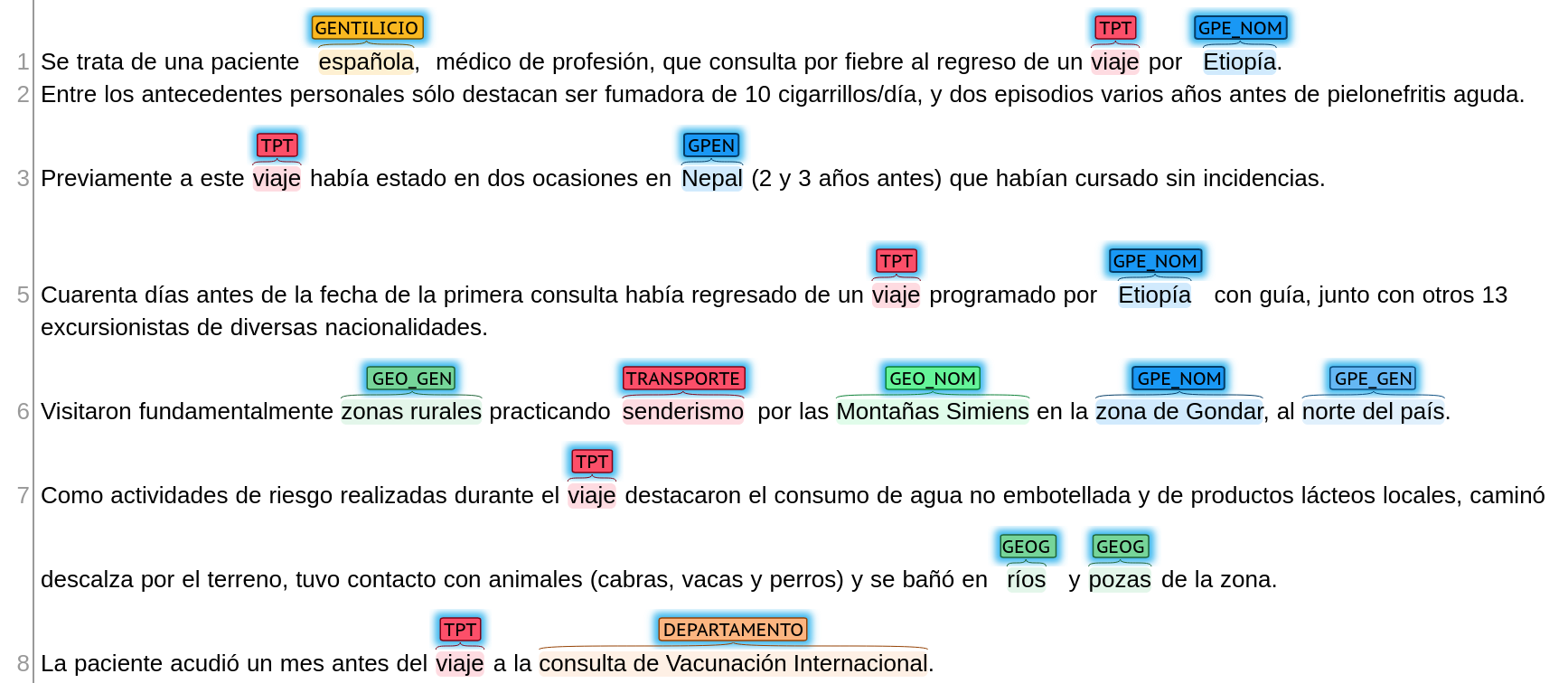

A Spanish female patient, a professional doctor, consulted for fever after returning from a trip to Ethiopia.

Her personal history included smoking 10 cigarettes/day and two episodes of acute pyelonephritis several years earlier.

Prior to this trip, she had been to Nepal on two occasions (2 and 3 years earlier), both of which had been uneventful.

Forty days before the date of the first consultation, he had returned from a scheduled guided tour of Ethiopia with 13 other hikers of various nationalities.

They visited mainly rural areas hiking in the Simiens Mountains in the Gondar area in the north of the country.

Risky activities during the trip included consumption of unbottled water and local dairy products, walking barefoot in the terrain, contact with animals (goats, cows and dogs) and bathing in local rivers and pools.

The patient attended the International Vaccination consultation one month before the trip.

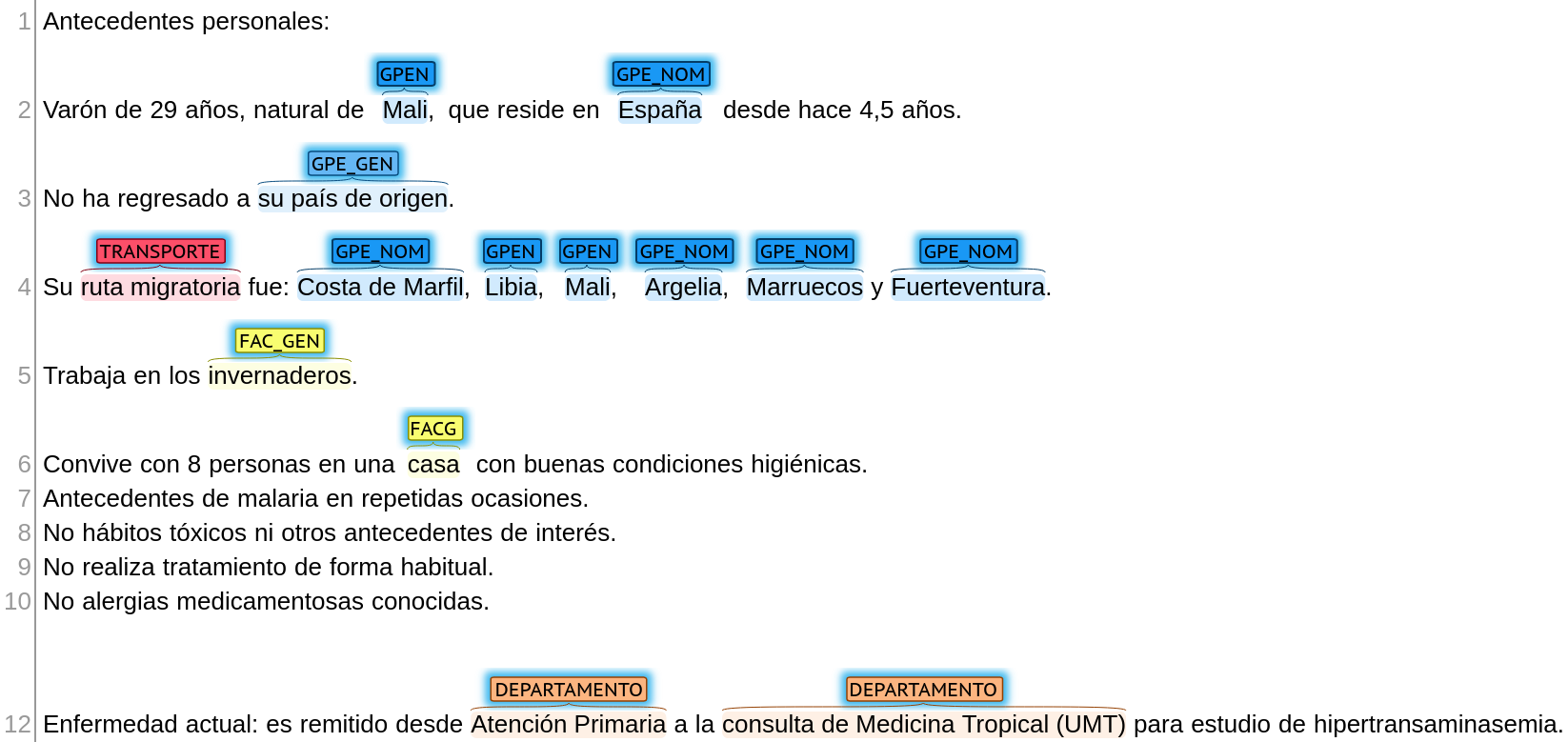

Personal history:

Male, 29 years old, from Mali, who has been living in Spain for 4.5 years.

He has not returned to his country of origin.

His migratory route was: Ivory Coast, Libya, Mali, Algeria, Morocco and Fuerteventura.

He works in greenhouses.

He lives with 8 people in a house with good hygienic conditions.

Repeated history of malaria.

No toxic habits or other history of interest.

No regular treatment.

No known drug allergies.

Current illness: he was referred from Primary Care to the Tropical Medicine Department (UMT) for a study of hypertransaminasemia.

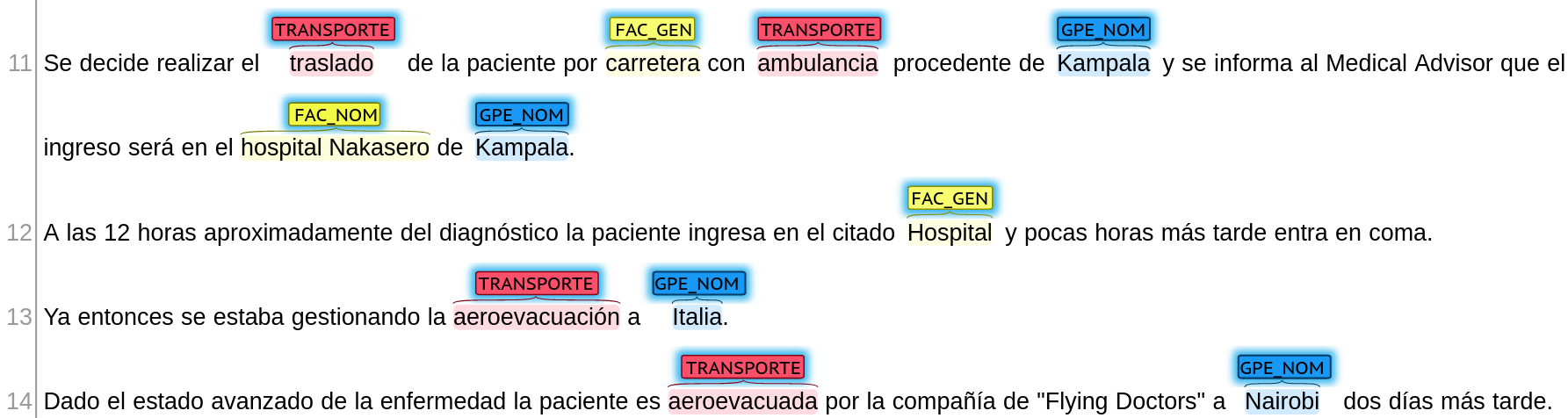

It is decided to transfer the patient by road in an ambulance from Kampala and the Medical Advisor is informed that the patient will be admitted to Nakasero Hospital in Kampala.

Approximately 12 hours after diagnosis, the patient was admitted to the aforementioned hospital and a few hours later went into coma.

Air evacuation to Italy was already being arranged.

Given the advanced stage of the disease, the patient was airlifted by the "Flying Doctors" company to Nairobi two days later.

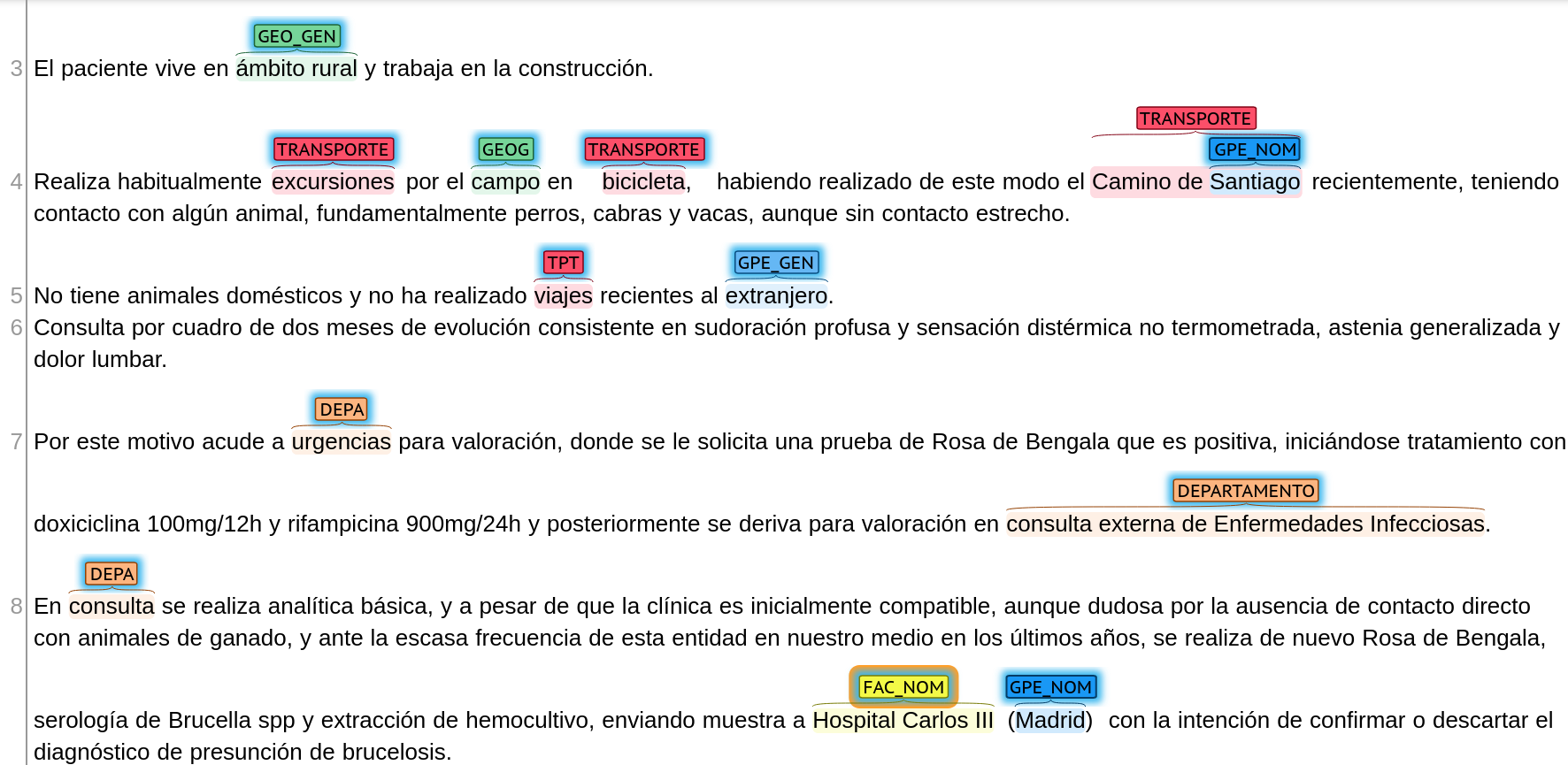

The patient lives in a rural area and works in construction.

He regularly goes on excursions in the countryside by bicycle, having recently cycled the Camino de Santiago, having contact with some animals, mainly dogs, goats and cows, although without close contact.

She has no pets and has not recently travelled abroad.

She consulted for symptoms of two months' evolution consisting of profuse sweating and non-thermometric dysthermic sensation, generalised asthenia and lumbar pain.

For this reason she went to the emergency department for assessment, where a Rose Bengal test was requested, which was positive, and treatment was started with doxycycline 100mg/12h and rifampicin 900mg/24h, and she was subsequently referred to the outpatient Infectious Diseases department for assessment.

Basic laboratory tests were performed in the doctor's office, and despite the clinical picture being initially compatible, although doubtful due to the absence of direct contact with livestock, and given the infrequency of this entity in our environment in recent years, Rose Bengal, Brucella spp serology and blood culture extraction were performed again, sending a sample to Hospital Carlos III (Madrid) with the intention of confirming or ruling out the presumptive diagnosis of brucellosis.

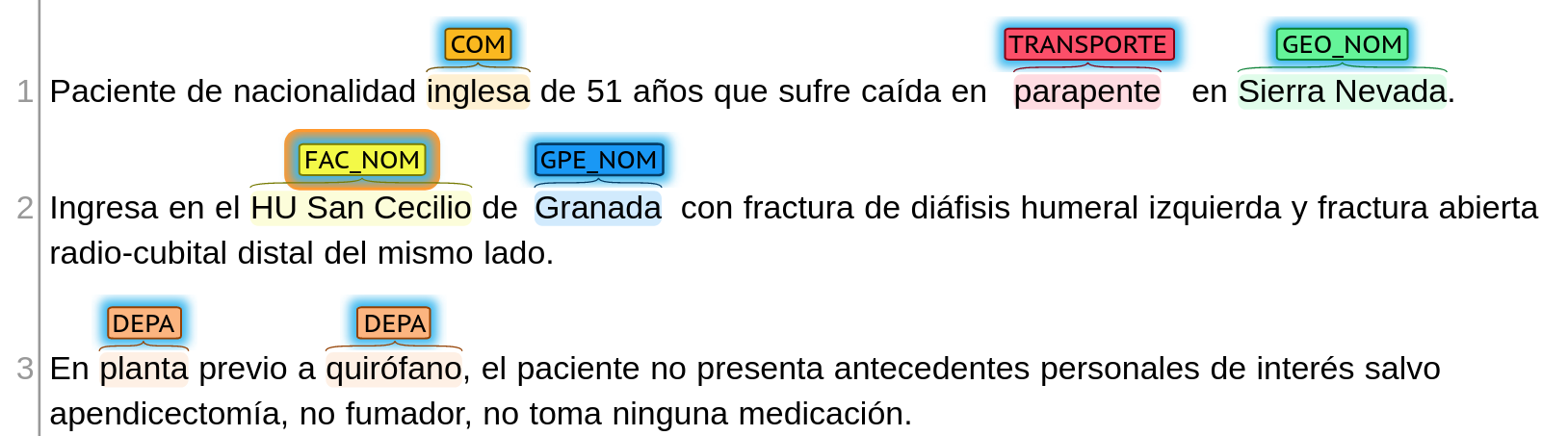

51-year-old English patient who suffered a fall while paragliding in Sierra Nevada.

Admitted to the HU San Cecilio in Granada with left humeral diaphysis fracture and open distal radius-ulnar fracture on the same side.

On the ward prior to the operating theatre, the patient had no personal history of interest except for appendectomy, was a non-smoker and did not take any medication.

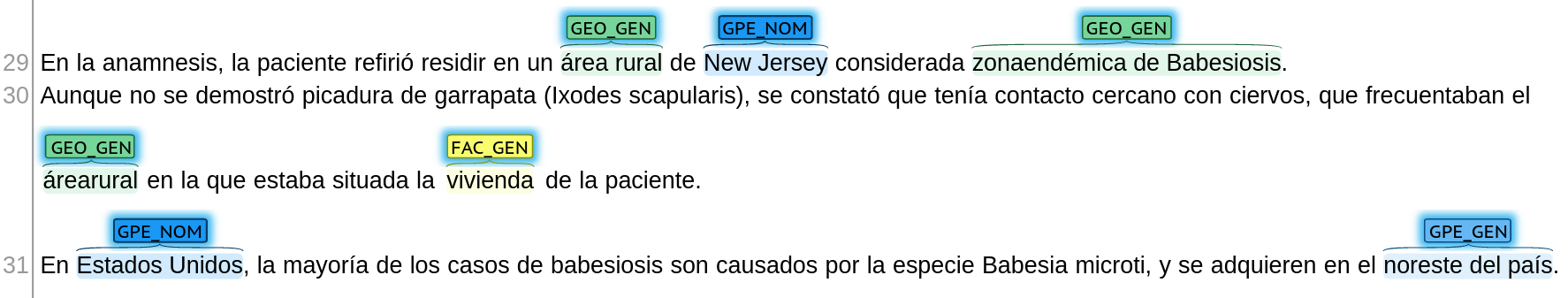

On anamnesis, the patient reported residing in a rural area of New Jersey considered to be a Babesiosis-endemic area.

Although no tick bite (Ixodes scapularis) was demonstrated, it was noted that she had close contact with deer, which frequented the rural area in which the patient's home was located.

In the United States, most cases of babesiosis are caused by the species Babesia microti, and are acquired in the northeastern part of the country.

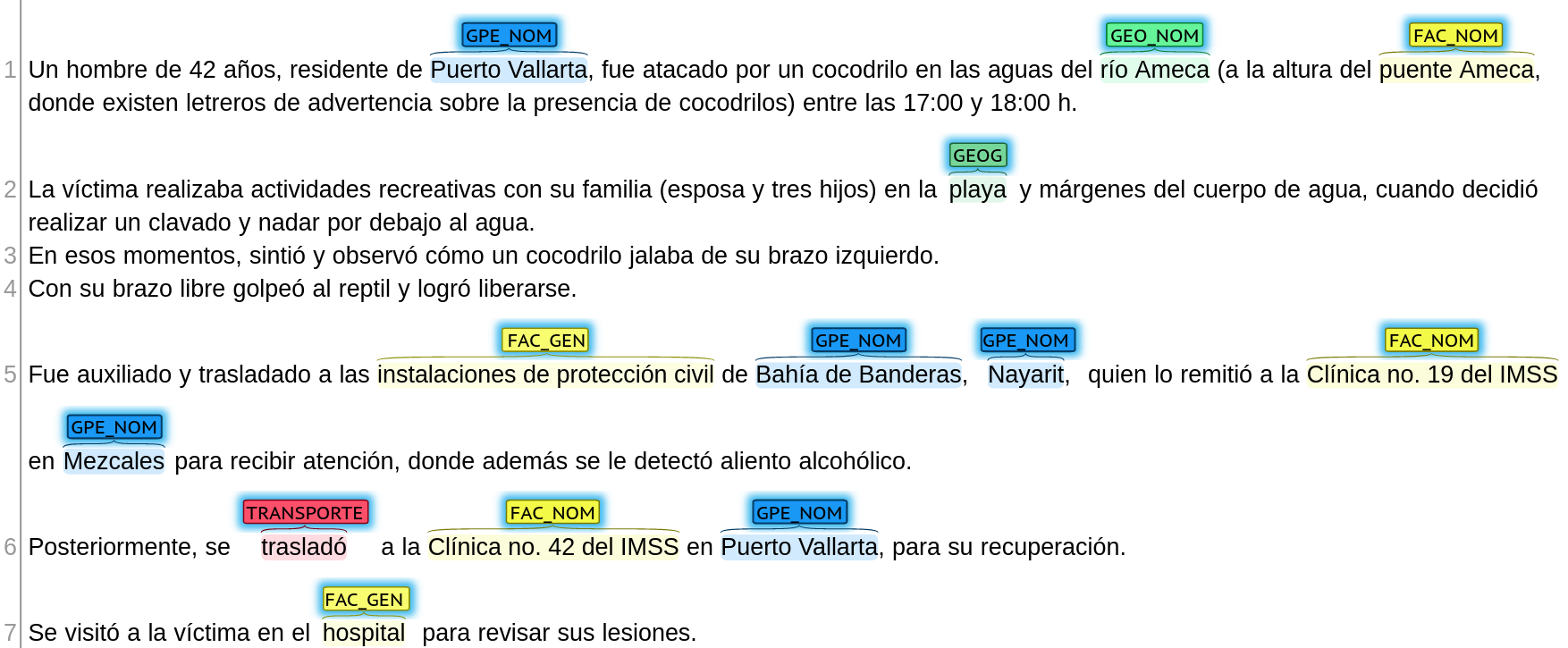

A 42 year old man, resident of Puerto Vallarta, was attacked by a crocodile in the waters of the Ameca River (at the Ameca Bridge, where there are signs warning about the presence of crocodiles) between 17:00 and 18:00 h.

The victim was engaged in recreational activities with his family (wife and three children) on the beach and banks of the water body when he decided to take a dive and swim under the water. The victim was engaged in recreational activities with his family (wife and three children) on the beach and banks of the body of water, when he decided to dive in and swim under the water.

At that moment, he felt and observed a crocodile pulling on his left arm.

With his free arm he hit the reptile and managed to free himself.

He was helped and taken to the facilities of the civil protection of Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit, who referred him to the IMSS Clinic no. 19 in Mezcales to receive attention, where he was also found to have alcoholic breath.

Subsequently, he was transferred to IMSS Clinic no. 42 in Puerto Vallarta for recovery.

The victim was visited at the hospital to check his injuries.

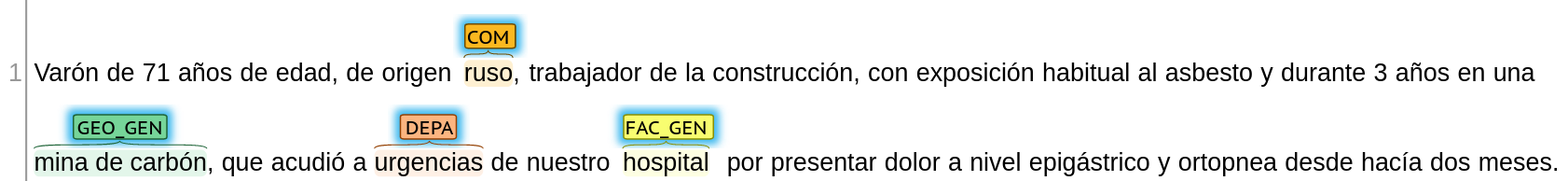

A 71-year-old man of Russian origin, a construction worker with regular exposure to asbestos, who had been working in a coal mine for 3 years, came to the emergency department of our hospital presenting with epigastric pain and orthopnoea for the last two months.

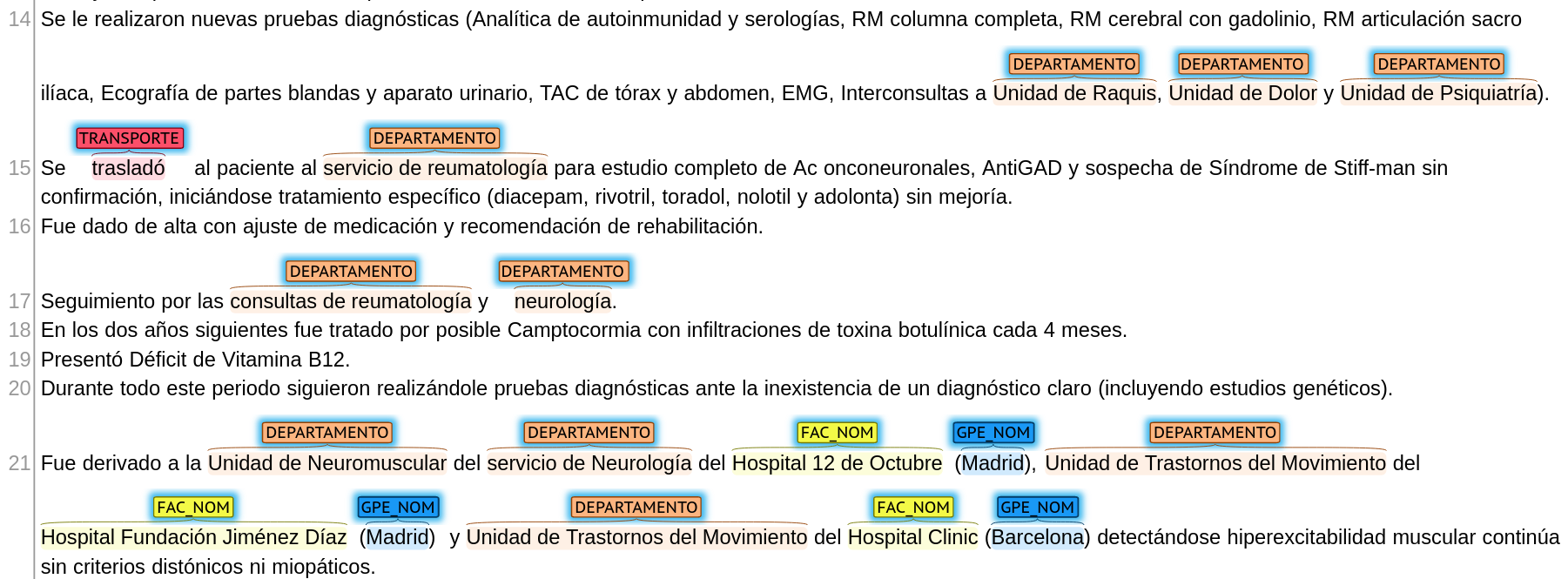

New diagnostic tests were performed (autoimmunity and serology tests, complete spine MRI, brain MRI with gadolinium, sacroiliac joint MRI, soft tissue and urinary system ultrasound, chest and abdominal CT scan, EMG, referrals to the Spine Unit, Pain Unit and Psychiatry Unit).

The patient was transferred to the rheumatology department for a complete study of Ac onconeuronal, AntiGAD and suspicion of Stiff-man's syndrome without confirmation, and specific treatment was started (diacepam, rivotril, toradol, nolotil and adolonta) without improvement.

He was discharged with adjustment of medication and recommendation for rehabilitation.

Follow-up by the rheumatology and neurology departments.

In the following two years he was treated for possible Camptocormia with botulinum toxin injections every 4 months.

He had a vitamin B12 deficiency.

Throughout this period he continued to undergo diagnostic tests in the absence of a clear diagnosis (including genetic studies).

He was referred to the Neuromuscular Unit of the Neurology Department of the Hospital 12 de Octubre (Madrid), the Movement Disorders Unit of the Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid) and the Movement Disorders Unit of the Hospital Clinic (Barcelona), detecting continuous muscular hyperexcitability without dystonic or myopathic criteria.

2. Normalization

Given the variety of information contained in the MEDDOPLACE corpus, three different sources had to be used to normalize the annotations. These are:

- GeoNames: a geographical database that provides a comprehensive and structured set of geographical data, including names, coordinates, and other related information about places all around the world. It is available for free and can be accessed through a web interface or downloaded for local use. GeoNames contains over 11 million place names and covers over 25 million unique locations worldwide, including populated places, land features, and other geographic points of interest, which is why it was used to normalize named geopolitical and geographical entities (GPE_NOM and GEO_NOM). Each location is assigned a unique identifier, which can be used to retrieve various types of information about the place. GeoNames data is used by various applications and services, such as geocoding and mapping services, travel and tourism websites, weather services, and research projects. More info on https://www.geonames.org/.

- PlusCodes: also known as Open Location Codes (OLCs), they are an open-source digital addressing system developed by Google. PlusCodes are designed to provide a simple and accurate way to identify any location in the world, even in areas where traditional street addresses are not available or not precise enough. They are free to use, available offline and can be easily integrated into maps, GPS devices, and other location-based services. PlusCodes can be used to identify and share any location, including hospitals, businesses, and landmarks, which is why they were used to normalize named facilities (FAC_NOM). More info on https://plus.codes.

- SNOMED CT: a comprehensive clinical terminology that is used to represent and encode clinical information in electronic health records (EHRs). It is considered one of the most comprehensive and widely used clinical terminologies in the world, with over 340,000 active concepts that cover a broad range of medical topics and related information. Due to its coverage, SNOMED was used to normalize the remaining entity types.

3. Classification

To allow for a clinically-oriented characterization of the locations mentioned in the text, every location in the text has been classified in one of five categories:

- Origin (LUGAR NATAL class): Used for locations that are mentioned to be the patient’s place of birth.

- Residence (RESIDENCIA class): Used for locations that are mentioned as the current or former place of residence.

- Movement (MOVIMIENTO class): Used for locations that are the destination or origin of a travel.

- Attention (ATENCIÓN class): Used for locations where the patient has received medical attention.

- Other (OTROS class): Used for locations that do not fit into any of the categories above.

References

- Doddington, G. R., Mitchell, A., Przybocki, M. A., Ramshaw, L. A., Strassel, S., & Weischedel, R. M. (2004). The automatic content extraction (ACE) program-tasks, data, and evaluation. In International conference on language resources and evaluation (vol. 2, p. 1).

- Weischedel, R.M., & Brunstein, A.. (2005). “BBN Pronoun Coreference and Entity Type Corpus LDC2005T33”. Web Download. Philadelphia: Linguistic Data Consortium.